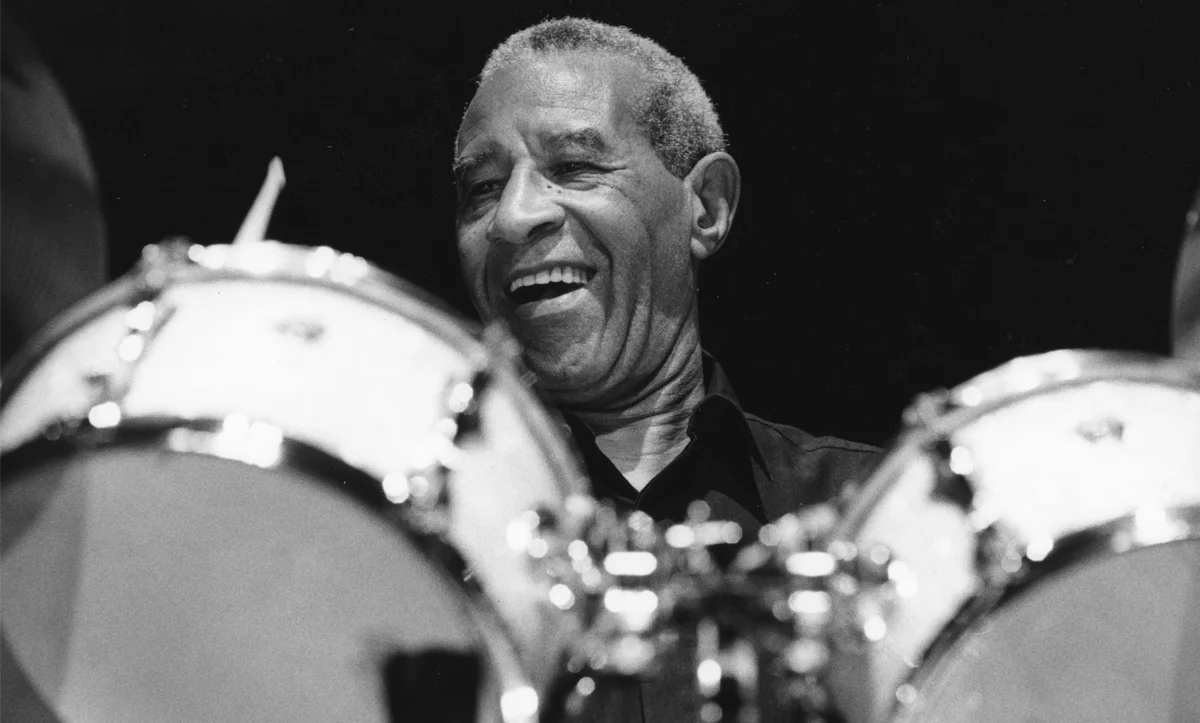

Max Roach: The Drummer Who Revolutionized Jazz

Considered a contributor to founding modern jazz, Max Roach was not only one the pioneers of bebop but also noted as one of the most influential drummers of all time.

His career has inspired so many other incredible drummers beyond his time. He was innovative in his approach to how drums were arranged and approached in music. Max was a music and civil rights revolutionary in the 1950s and 1960s.

He shaped a new drumming style so much that he was one of the first artists to turn his unique approach as an instrumentalist into a business of his own instead of just performing for other artists. Below we take a look into the life and career of Max Roach and how he dominated percussion in the 20th century.

Young Max

Roach’s beginnings were humble. Like many African Americans during that time, he was born into poverty in the south. When his family moved to Brooklyn, NY, and joined a church, Roach began to discover a fascination with music.

Roach didn’t just have to go to church to hear wonderful music. Music had a significant presence inside his home as well. His mother was a gospel singer who often sang in church, and his brother played the horn in the school marching band.

After being inspired by the musicians around him, Roach tried to play the horn at age ten like his brother but didn’t grasp it well, so he took up the drums at school. At age 12, his dedication to the drums was strong, so his father bought him his first trap kit, and he soon played in church and other gospel bands. As he grew up, he continued to improve and played for different jazz bands.

Early Career

By the time Roach was 18, he had begun playing drums professionally. While in Manhattan, he was asked to be a substitute for the great Duke Ellington and the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Paramount Theatre.

He did so well with that performance that he became a popular drummer in many jazz clubs in New York along 52nd Street. During this year, he also played at the then-popular Georgie Jay’s Taproom with Cecil Payne on 78th Street and Broadway.

By 19, he became a regular and Monroe’s Uptown House and played with musical legends such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. In 1943 Roach made his first recording as a drummer with saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and his quintet.

As he continued in the 1940s, he was the first drummer to play along with jazz drummer Kenny Clarke. Together they developed what is now called bebop-style jazz.

Bebop jazz is different from other jazz styles because most jazz is soft, calm, and controlled. In contrast, bebop was loud and exhilarating with faster tempos, making the listener excited and wanting to move.

The drumming technique that Clarke pioneered was an aggressive style with complex patterns. Some of these patterns may have an off meter, but the groove is kept with consistent cymbals.

The technique allows drummers to play more freely and add their own style and accents to cymbal and snare drum. During this time, not only did Roach begin to play in bebop style, but he also developed a strong technique with brushes and played with bands by artists mentioned earlier and Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, and more.

Becoming Famous

As Roach kept playing with bands, utilizing his unique brush techniques and bebop drumming style, he became a recognized musician. Finally, in 1945 he approached the one performance that would solidify him as one of the most recognized and notable drummers.

On June 22, 1945, Roach performed at the Town Hall Concert in New York with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. While those two were the headliners, Roach unintentionally stole the show from the beginning.

The first few measures of the opener “Bebop” allowed him to display all of his evolved modern bebop skills. Although the show was recorded, those who attended the show were the only ones who could hear the session because the recording was put on the shelf for over 60 years.

Word of mouth is how the high praise of Max Roach helped him begin to see fame. In 1950 he studied music at the Manhattan School of Music, working to earn a bachelor’s degree. While learning in Manhattan, he also started a record label with a bassist named Charles Mingus. The label was fittingly called Debut Records.

On this label, he recorded “Jazz at Massey Hall,” and he recorded and released “Percussion Discussion,” a bass and drum improvisation performance.

During this time, he also formed a quintet with Clifford Brown, Harold Land, Richie Powell, and bassist George Morrow. This group spread the bebop style of jazz and led it to continue to grow.

Working with Miles

Another prominent time in Max’s career was working with the legendary Miles Davis. He was the main drummer on the album that defined the “cool jazz” movement, and that album was “Birth of Cool.”

On this album, Roach plays on seven of the tracks. When Davis, Roach, and the rest of the band played these recordings live, many critics didn’t consider it jazz. Due to Roach’s different approach to drumming, they thought it to be an impressionist style of music. This sparked the term “cool jazz movement,” making others look at Roach as an innovative drummer once again.

Drums and Civil Rights

Roach saw that having a career and being African American had challenges in the 50s and 60s. He used his percussive talents as an outlet to fight in the civil rights movement. He created an album entitled “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite,” — a body of work addressing the political and cultural injustice that African Americans went through at that time.

Roach used this album and his performances as his voice for African Americans in every community, especially African American musicians. Black musicians were not receiving the same pay as other musicians — if they were paid at all.

Roach began to dedicate every performance to advocate for his and other African Americans’ rights. It wasn’t just about the love of music anymore.

Education and New Discoveries

After two members of his quintet Clifford Brown and Richie Powell, were killed in a car crash, Roach had to regroup and continue to record with new musicians. Amongst recording, he discovered a new innovative approach to the traditional bop percussion rhythms.

He began to use ¾ waltz rhythms within his performances. This led him to record the album “Jazz in ¾ Time.” Throughout the rest of the 1950’ through 70’s he continued to record albums and perform.

His notoriety became so prominent that the Lenox School of Jazz recruited him to teach jazz education along with a few other famous jazz musicians, such as Dizzy Gillespie, until the school closed. Later in 1972, he taught jazz education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst until 1992.

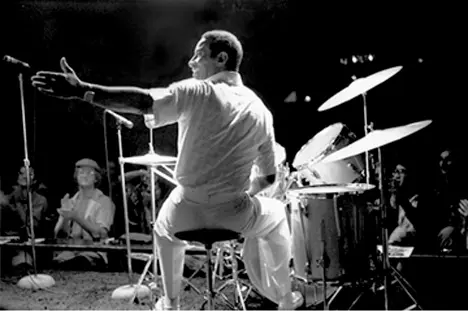

Percussion Ensemble

In the late 1960s, Roach recorded what many considered his best album, “Drums Unlimited” on this album, he continued to demonstrate his well-known improvisation skills.

Most of the tracks on this album, however, consisted of drum solos. This led Roach to a new drum venture. During the 1970s, Roach formed a percussion ensemble called the M’Boom, consisting of ten different percussion players—every member composed songs comprised of parts for several other percussion instruments.

Together the M’Boom performed for over 30 years. Their productions included different elements of African percussive sounds and other percussion elements from around the world. They also created some classical music and, of course, jazz. The ensemble was so successful that his last recorded performance was with the ensemble.

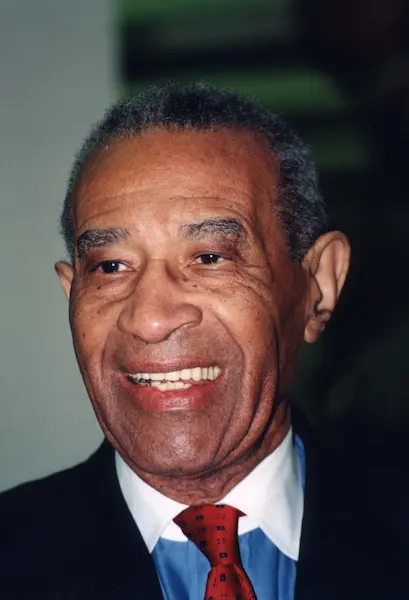

Final Years

From the late 70s until the early 2,000s, Roach continued to release another two dozen plus albums where he worked with any new jazz artists who were making a career for themselves.

Some of these artists were Clark Terry, Cecil Taylor, Eddie Henderson, and more. In 2003 Roach played for the last time at his 50th anniversary live performance. In 2009, a few years after his death, he was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame.

His other prominent accolades included an award for Harvard Jazz Master, the International Percussive Art Society Hall of Fame, eight honorary doctorate degrees, and many more. To many during his time, he was said to be one of the most influential drummers to hold a pair of sticks. The significant impact that his slight change in elements on a trap kit continues to influence many drummers today.